The pictographs in Naj Tunich cave rocked the world of Maya archaeology world when they were discovered in 1979, fueling fresh research into the importance of caves as sites of Maya pilgrimage and worship. Today, the importance of caves -and the symbols they contain- to pre-contact Mesoamerican belief systems seems obvious. Back then, the notion was revolutionary.

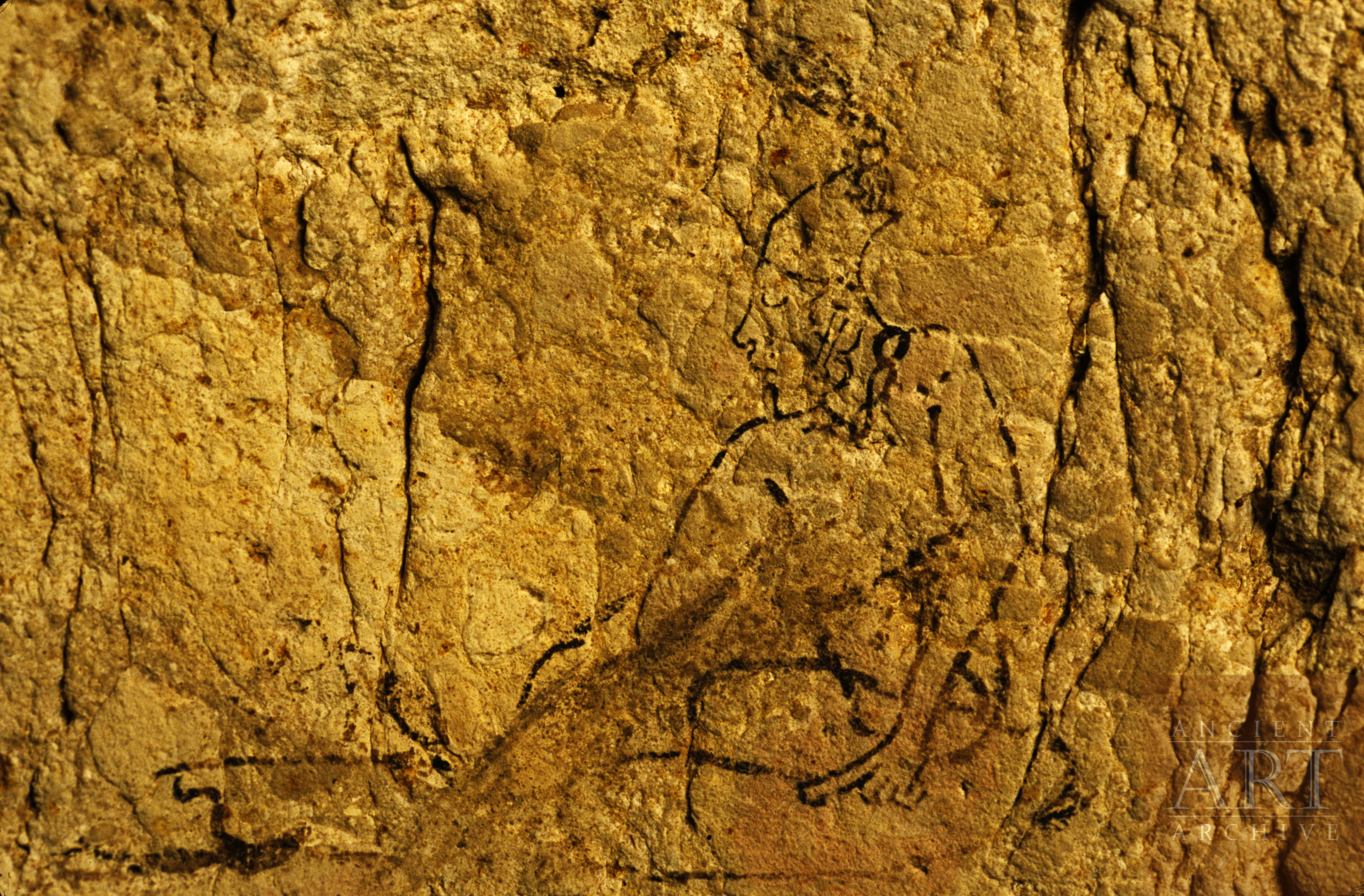

Naj Tunich cave is located near the town of La Compuerta in the Peten of Guatemala. The artwork inside is about 2,000 years old. The original artists created their delicate images with black paint that hasn’t completely dried. Sadly, much of the artwork in the cave was destroyed in a labor dispute shortly after its discovery. The Guatemala Government sealed the cave to protect what remained.

I went to Naj Tunich solely to photograph the artwork. Awe overwhelmed me as I entered the cave and stood before the surviving paintings. But what surprised me most on that trip was being surrounded by machete-toting residents of La Compuerta when I left the cave one evening. They insisted I attend a harvest ritual in the coming fall. None of them had ever entered the cave, but they understood it as a place of power and an important ritual space.

It felt like an offer I couldn’t refuse, so I returned. The ritual itself began in the evening. Don Vicente Cucul maintained the town’s Maya calendar. He prepared the ceremony, assembling offerings of copal incense, candles, tobacco, herbs and liquor that would be sacrificed the following dawn. In his house, fragrant copal burned. Men and women prayed over the offerings. Music, dancing, feasting, and laughing lasted all night.

At dawn, Don Vicente gathered the offerings, took the fire from his house, and led a procession to the cave. On the cave floor he laid out a cross in granulated sugar, the lines of the cross corresponding to the cardinal directions. He poured a sugar circle around it—a model of the world with offerings of herbs, copal, candles and tobacco laid on top. Men and women intoned prayers to the four directions, then lit the offerings on fire.

As the fire spread, men danced around the swirling fire, throwing seeds into the blaze.

The cave’s huge entrance chamber filled with smoke. The people made their way slowly out of the cave and returned to town.

The Maya of La Compuerta are thoroughly modern people. They aren’t living in the past. Their connection to Naj Tunich and Maya worship is a living belief that coexists with their Christian faith and helps define a connection to deep culture. I was left feeling that the artwork inside the cave provides a direct connection between the modern Maya and their predecessors.

Even though they live by the cave, none of the residents of La Compuerta has ever seen the artwork their forbearers had created within. One of the animating ideas of the nonprofit Ancient Art Archive is to provide digital access to inaccessible cultural history. This is particularly relevant in the United States, where many descendent communities were forcibly removed from the homelands that contain the art and cultural sites created by their ancestors. The Ancient Art Archives’ 3D model and virtual reality video of Devilstep Hollow Cave in modern Tennessee allows today’s Chickasaw—who now live in Oklahoma—to experience a visual story told by their forbearers. It is our hope that the digital images of Naj Tunich that we have in our online archive will help the people of La Compuerta connect with the artwork inside the cave.

Rescources:

Images from the Underworld -Andrea Stone

Online Popol Vuh Translation by Alan Christenson

Ancient Art Archive Naj Tunich images

1,200-year-old Children’s handprints a Maya Cave

Additional Naj Tunich images