Indigenous Cave Explorers ventured as far as three miles into southeastern caves 5,000 years before the invention of electric light.

Caves are eerie and dangerous places imbued with strange power. In the “twilight zone” near a cave entrance, light filtering in from the surface creates a gloomy illumination. Not one iota of light penetrates the “dark zone” beyond the reach of surface light. In the dark zone, the darkness is so complete a person can’t tell whether their eyes are open or closed. In any era, cave exploration requires courage, specific skills, a unique mindset, and a portable light source. Underground without a light source, homo sapiens is a helpless animal. No competent modern caver would dream of entering a cave without two reliable sources of light, one an LED capable of providing some 70 hours of illumination.

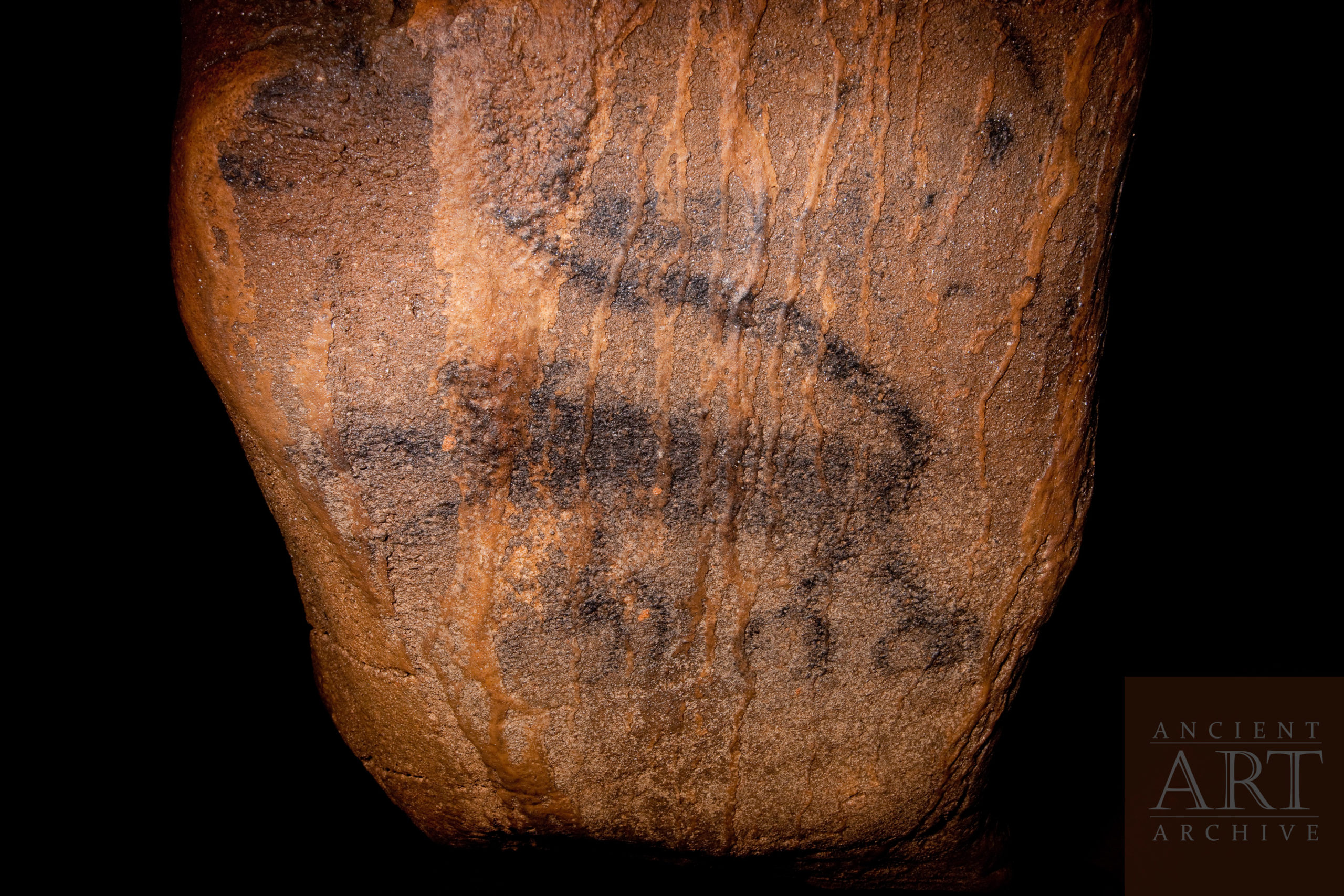

Astoundingly, Indigenous cave explorers ventured as far as 3 miles into southeastern caves 5,000 years before the invention of electric lights. Those intrepid Indigenous cave explorers lit their way with smoky cane torches, and they reached locations deep within caves that hardcore modern cavers find difficult to attain. We know Native Americas reached those places for a variety of reasons. The black splotches where they “ashed” their cane torches to reduce the amount of smoke the torches emitted are common underground. (The residual material of these “stoke marks” can be carbon dated with remarkable precision.) Far underground, modern cavers also occasionally encounter supplies of unused cane torches that Native Americans cached to springboard deeper explorations and allow them a re-supply on their way back to the upper world.

The mud floors of certain caves also still preserve indigenous footprints, bare footprints belonging to men, women, and children. In one case, a toddler made one set of ancient footprints found far underground. In another there is a footprint in a chamber that also contains cave art.

What exactly such a plethora of Indigenous persons were doing in caves is hard to know with certainty. In some places, they mined gypsum deposits, in others they mined flint nodules they could knap into stone tools, but in most places, archeologists and cavers can’t determine what the Indigenous persons were doing despite indisputable evidence of their presence.

Make no mistake: underground exploration is dangerous. Modern cave explorers sometimes pay with their lives. Indigenous cavers did, too. Modern cavers discovered the body of an Indigenous gypsum miner crushed beneath a boulder more than 2.5 miles from the entrance of Mammoth Cave, Kentucky. The unfortunate fellow’s body had been there for 5,000 years. [More here] In another cave, Indigenous cavers explored nearly 10 miles of underground passages. Dead bodies have been discovered in nine separate locations in that cave, all of them some four or five hours of underground travel from the cave entrance. None of the bodies show evidence of violence or of being intentionally interred. The circumstances of their deaths make it seem most likely that their cane torches failed. Lost in the dark, many hours of travel from the cave entrance, those nine individuals died before they could grope their way to safety.

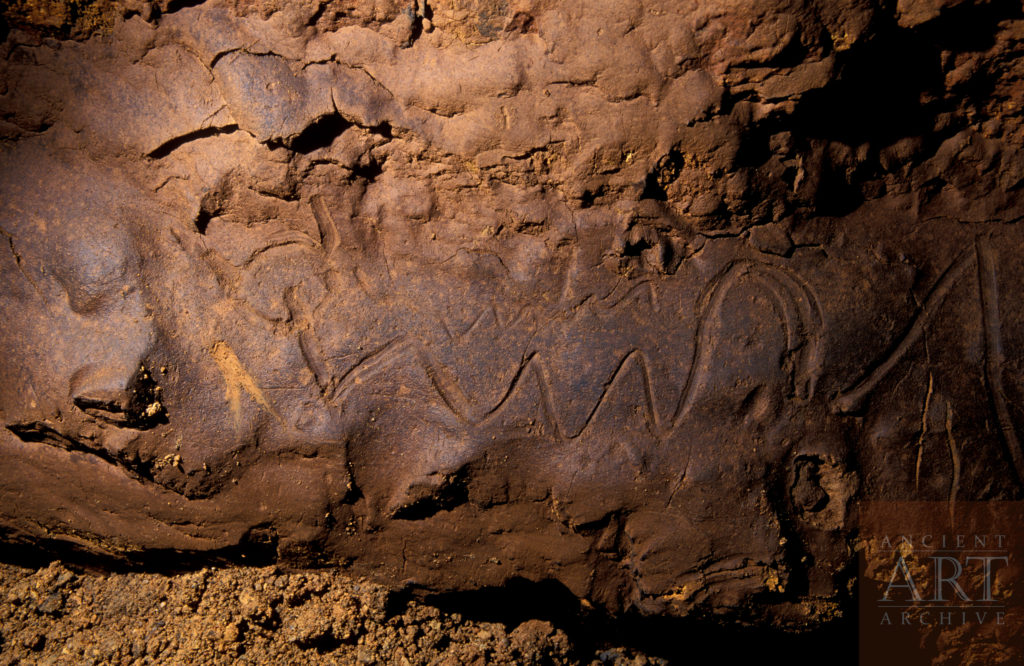

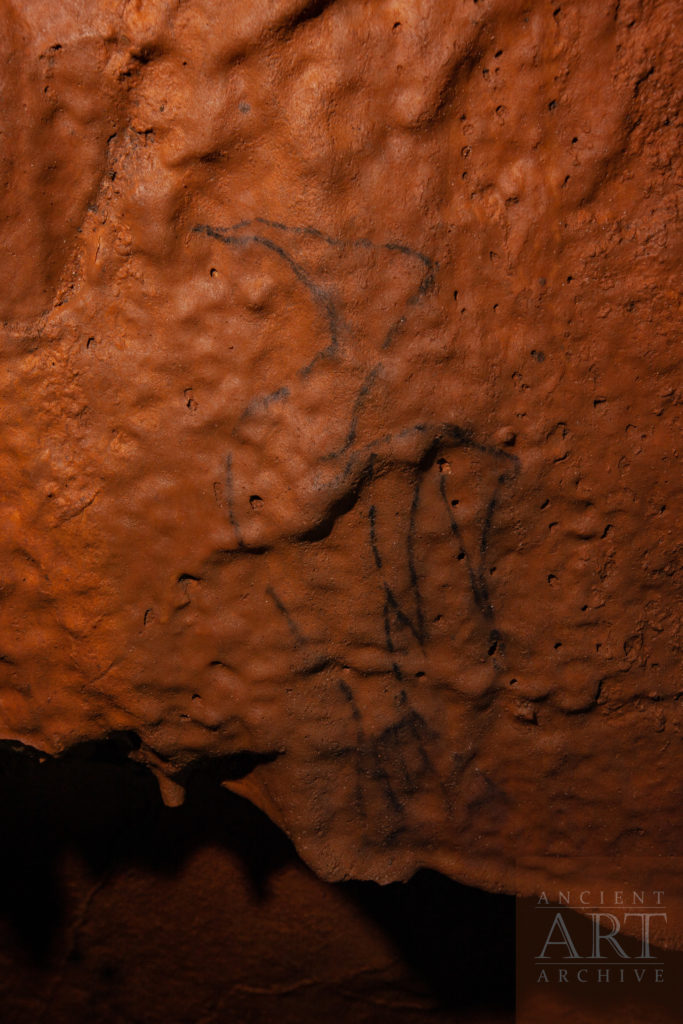

Except in places where Indigenous cave explorers left evidence of their mining activity, we don’t know for certain what compelled them to embark on such epic underground travels. Perhaps they embarked on vision quests, making visits to the underworld to accumulate spiritual power, or just traveled underground for the sheer joy of exploration and adventure. There’s no way of knowing. But that Indigenous Americans undertook astonishingly serious cave explorations isn’t in doubt—the evidence is overwhelming—and they did it through a period of thousands of years. And sometimes they created art while they were underground.

Modern cave explorers first noticed underground Indigenous artwork in 1979. Since then, Indigenous dark zone art has been encountered in nearly a hundred southeastern caves. One of those them is Devilstep Hollow Cave, located in northeastern Tennessee’s Cumberland Trail State Park.

See our virtual guided tour of Devilstep Hollow Cave with Native American artists Dustin Mater HERE.

Resources:

Pre-Contact South East United States cultures

Dunbar Cave State Park, Tennessee