Devilstep Hollow Cave, Tennessee

This 360-degree fly-through video was narrated by artist Dustin Mater, citizen of the Chickasaw Nation. It’s best when viewed through a VR headset, but you can still enjoy it — and even move around within the video — on a regular screen.

Devilstep Hollow.

One of the best and most significant examples of Indigenous dark zone cave art in the southeastern United States is found in Devilstep Hollow, where images made a thousand years ago adorn what seems to be a complete ceremonial space. The panels of petroglyphs, pictographs, and mud glyphs in Devilstep Hollow tell a story related to the religious beliefs of the Mississppian people in much the same way that artwork in a modern church aims to shape the experience of visitors and open their hearts to a larger spiritual experience.

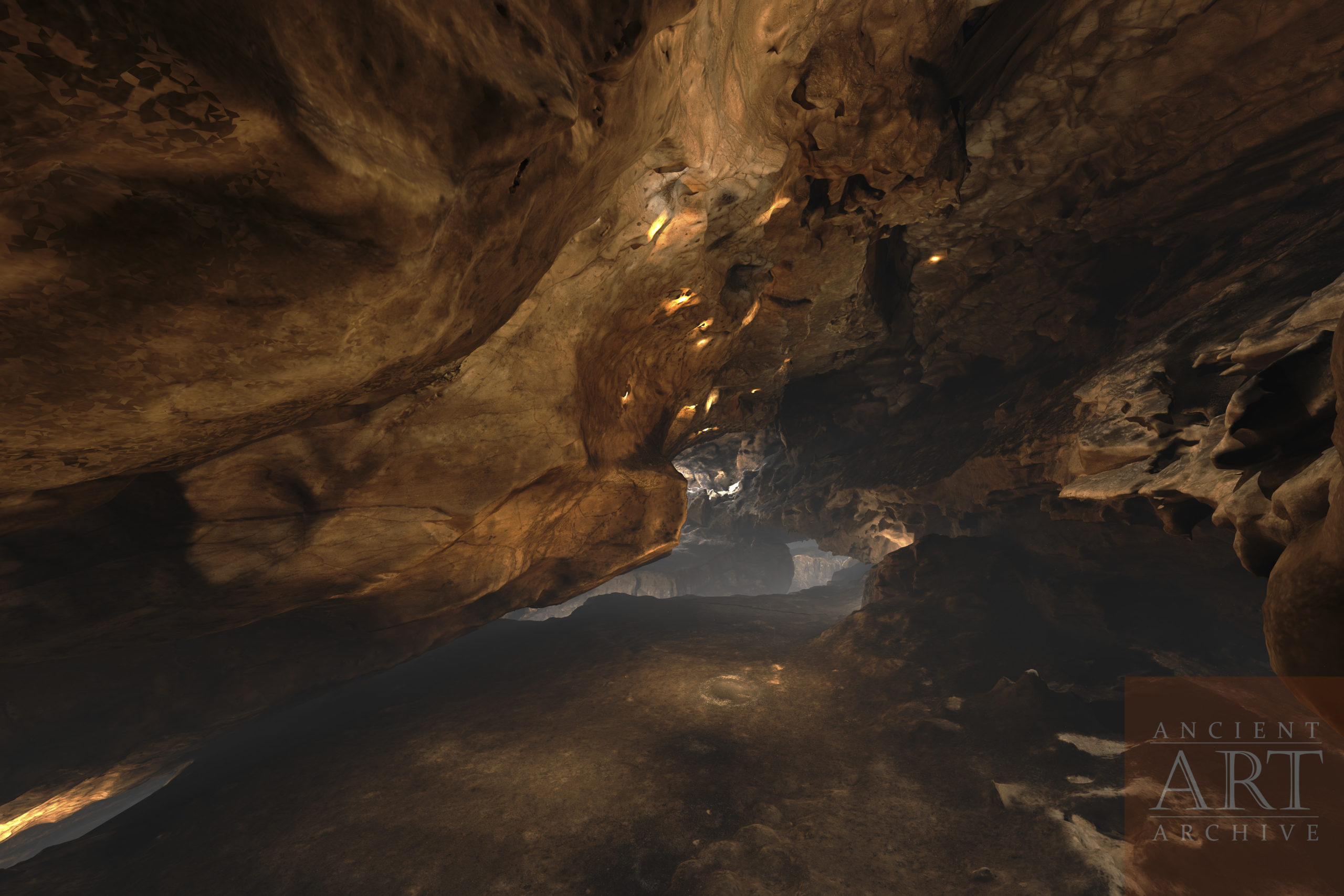

The setting of Devilstep Hollow is glorious, at the headwaters of the Sequatchie River. Lush eastern deciduous forests carpet the surrounding mountains. An easy scramble into a sinkhole reveals the looming cave mouth. Inside, in the twilight zone lit by filtered daylight, a shelf leads around a pool of still water. On the far side of the pool, a brow of rock caps a low opening. The empty blackness beckoning from under the rock overhang presents an obvious entrance to the underworld.

Mississippian peoples divided the universe into three realms: an upper realm of sky creatures and sky spirits like the thunderbirds, a middle realm of earth on which we live with all the other terrestrial flora and fauna, and an underworld beneath. The underworld spirits controlled life and death and provided a pathway through which the souls of the dead were led on their journey to the stars. Woodpeckers served as the guides who ushered dead souls along that path.

Into the cave.

A few hundred feet inside the cave’s entrance, in utter darkness, the ceiling lowers. Penetrating further requires a belly crawl through a body sized opening. The ceiling rises, allowing supplicants to rise into a stoop. After advancing in a low crouch, the passage opens into long hallway. Soon after an adult can stand to full height, the first Devilstep Hollow petroglyphs appear.

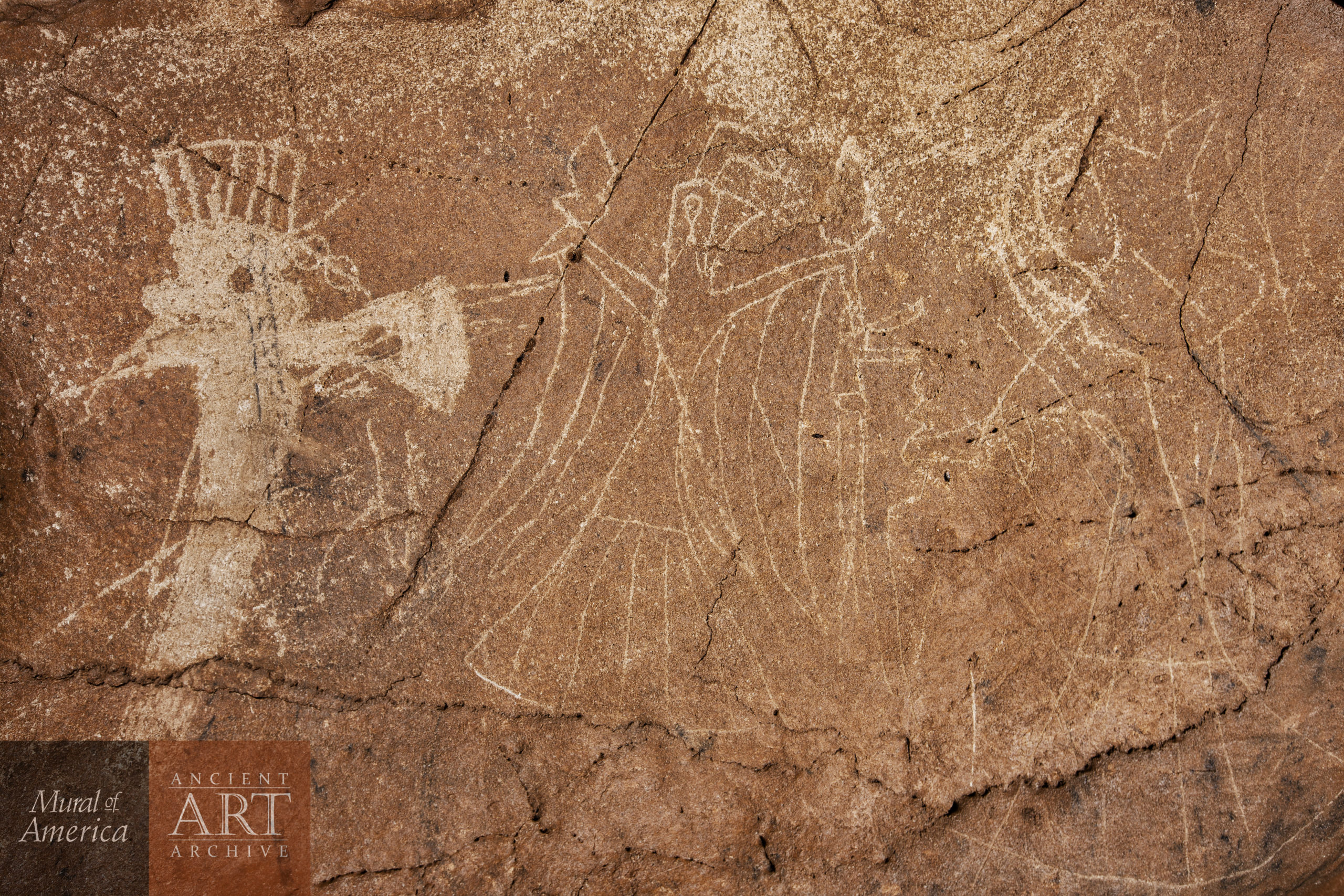

Flying as a pair, two woodpeckers point the way further into the cave, where a major panel presents four important images.

The first is of an axe or adze. Atop the shaft of the weapon is a human head. The axe blade emerges from the head. A bun of hair is collected at the back of the head. A forelock rides above the forehead. Taken together, the glyph comprises a classic Mississippian warrior image.

Next to the axe glyph rears the most famous figure in the cave, an upright bird with outstretched wings or arms. At the wingtips, each hand clutches a mace, which were both Mississippian weapons and symbols of priestly authority. Mississippian peoples would have instantly recognized the glyph as representing the Falcon Warrior, also known as Red Horn or Morning Star. The Falcon Warrior was a prominent figure in the continental belief system that spread during the Cahokian diaspora from the Great Lakes to the Gulf Coast and from Appalachia across the Mississippi River. (There’s another image of Red Horn in Missouri’s Picture Cave, and he’s a familiar figure in many stories told by modern communities descended from Mississippian culture, among them the Creek, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Seminole, and Natchez nations.)

The subsequent panel shows a face with serpents for eyes above a toothy rictus grin. Wavy lines descend from the image, like the head has been severed from an unseen body or perhaps demonstrating that it’s a disembodied spirit existing apart from any material form.

A large underworld fish emerging from the water appears beyond the rictus grin. The image is more than two meters long. Fins alternate above and below a slender body that culminates in a long, sharp-toothed snout. Reminiscent of an alligator gar, the fish is clearly not one of this world.

All of these symbolic images, most of which combine aspects of objects, animals, and humans, are inscribed upon the uneven surfaces of the cave walls. As those who entered the cave moved through with their cane torches, the irregular surfaces and flickering light would have animated the multi-faceted images, creating the illusion that they were moving, changing, transforming. The images and their placement set the stage as an entrance to a flat-floored area that may have been used for ceremonial purposes.

In the largest room of the cave, a plethora of cane torch material litters the floor and little mud balls cling to the ceiling overhead. The mud balls once held burning cane torches that filled the chamber with flickering light. Water sometimes flows along the side, providing the only sound. We can only imagine the transformative stories and rituals that might have been experienced in this space, and wonder about their individual, community, and spiritual significance.

A scramble up a breakdown pile at the rear of the room leads to a shelf and reveals the final artwork in the series. Another woodpecker flies above the shelf, and although this bird is drawn with charcoal rather than etched into the living rock, It’s oriented just like its two compatriots, showing the way further into the cave. A single Indigenous footprint remains in the mud on the shelf. Beyond, the cave continues deeper into the underworld.

Location map.

The cave is closed to public visitation but the trip to the sinkhole entrance is well worth the visit. The cave is part of Tennessee’s Cumberland Trail State Park.

Additional images.

Additional images from the cave and State Park and line drawings of artwork in the cave.

VR models.

We conducted a full interior scan of the cave, made from 5,188 Sony A7III images processed in Agisoft Metashape. Explore the Falcon Warrior section of the 3D model below.

The final room in the cave contains a drawing of a single woodpecker drawn in black charcoal. The room is extremely constricted and the artist would have needed to kneel down in order to paint make this drawing.

The original scan has over 85 million faces, and can be explored in the 3D model below, which has been decimated to 250,000 face and 5 textures to make it viewable online. The whole cave is over 110 meters long and there is a human footprint in the final passage from the cave’s ceremonial use in the Mississippian period.

The model was made with the support of Tennessee State Parks, Tower Community Bank, The Lyndhurst Foundation and the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Produced with funding from

Tower Community Bank

Trust for Historic Preservation

Lyndhurst Foundation