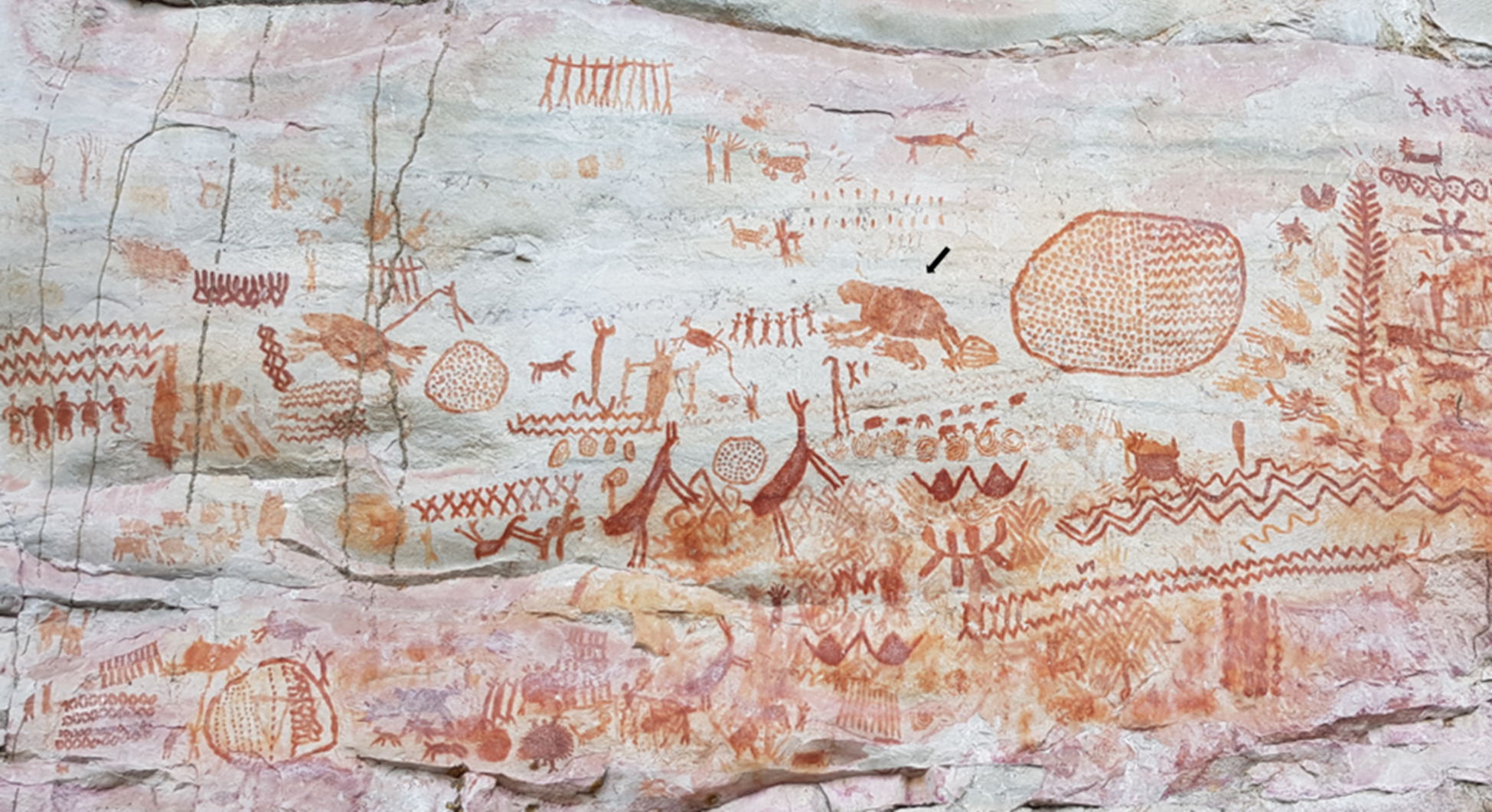

A new paper in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B (here) makes the case that the several of the pictographs in Serranía de la Lindosa, Colombia are depictions of long extinct megafauna.

A perplexing issue in the rock art of the Americas is the relative scarcity of depictions of paleolithic megafauna.

We know that humans have thrived in this hemisphere for more than 21,000 years. From the archaeological record we also know that the first humans here encountered and hunted megafauna -mammoths, giant sloths, camelids- But where are the depictions of those animals in the rock art of the continents?

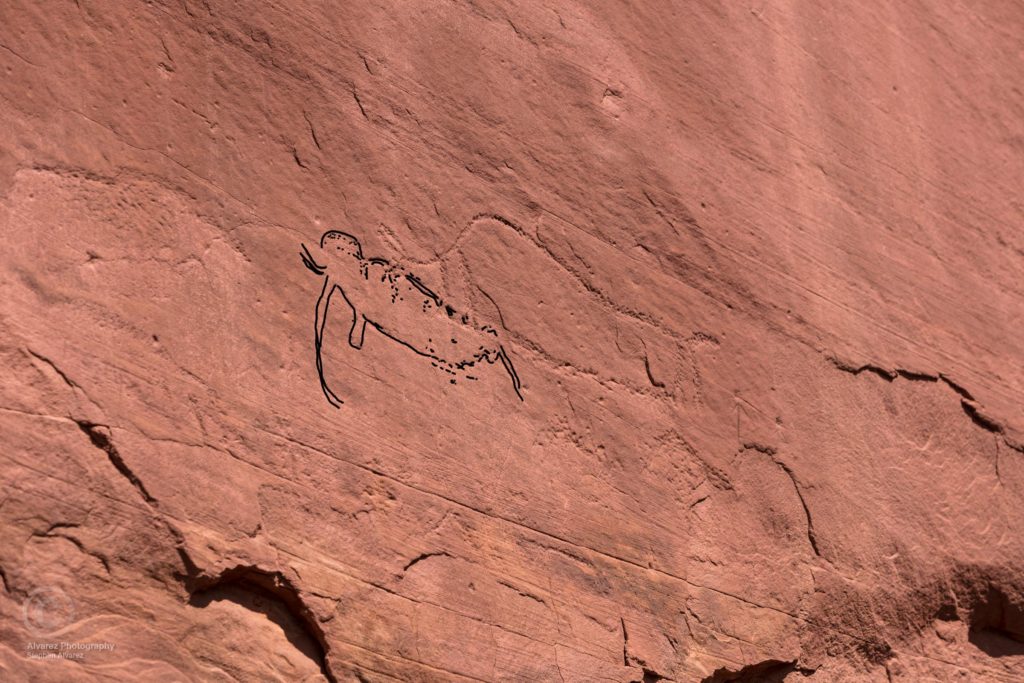

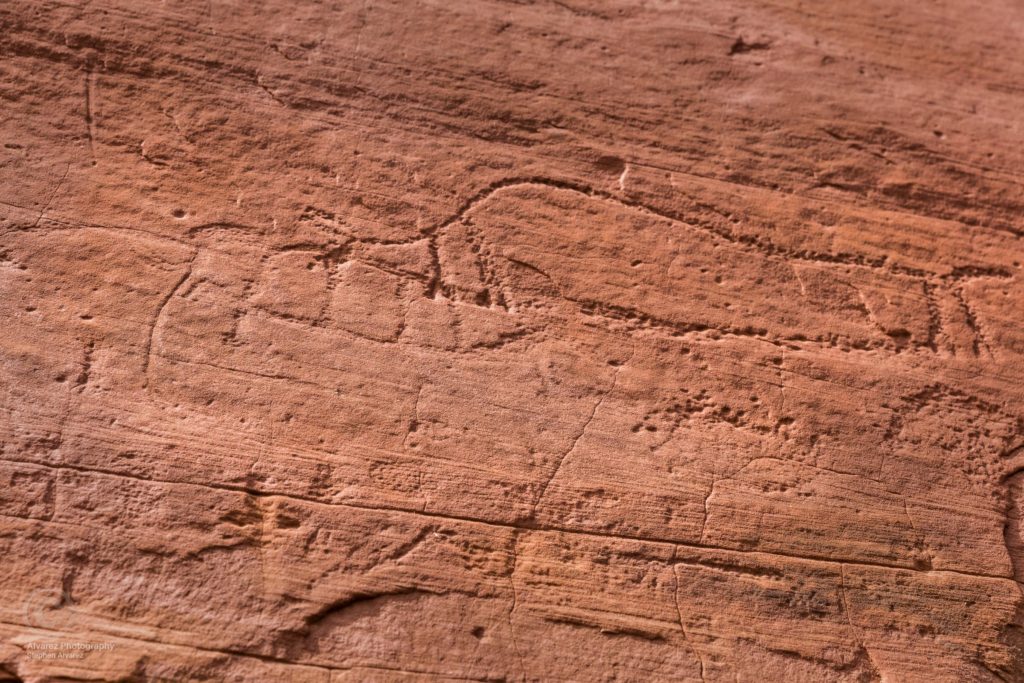

There are a spare handful of known depictions of ice age animals represented in the rock art of the Americas. The Sand Island Utah Mammoths (below) are the best known and perhaps the most controversial.

Sand Island mammoth petroglyphs, Bears Ears National Monument, Utah.

The images above illustrate the primary issue with seeing rock art images of great antiquity -they are hard to see! Open rock walls are terrible preservation environments and paintings fade over time. Usually, it is only petroglyphs that last.

The authors of the Royal Society paper use morphological analysis of the images to reach their conclusions. That is to say, the authors look at selected figures in the paintings and consider if they are compatible with what we know of paleolithic animals. Those are the same methods that Ekkehart Malokti used to argue for paleolithic origins of the Sand Island, Utah mammoths. As in the case of the Sand Island Mammoths, there is no physical evidence that humans interacted with ice age megafauna at Serranía de la Lindosa. The 12,000 year old deposits do not contain the remains of ice age megafauna.

Rock art is notoriously hard to date and there are incredibly old dates from physically associated archaeological remains at Serranía de la Lindosa that align with Paleolithic origin of the pictographs. There are red ochre artifacts from the sites that are definitively 12,000 years old. What is missing is any concrete connection between the paintings and those red ochre artifacts or any explanation for the fabulous preservation of the images. One of the things that rock art sites often point to is a “persistence of place.” Good places and important places remain good and important places across cultures. Some of the European caves were painted over 20,000-year periods, and sites like Three Rivers in New Mexico span multiple cultural complexes.

In the paper the authors say

Unlike the Upper Palaeolithic artists of Europe who chose to paint in deep dark caves, these early Amazonians painted in open rock shelters.

What is missing from that statement is an understanding that European Paleolithic artists likely painted on every available surface -cliffs, trees, rocks, skins, each other. We only think of them as cave painters because caves are the only places where their images survived the ravages of time. There are plenty of open-air rock art sites from the Upper Paleolithic in Europe. They contain petroglyphs, not pictographs. Paintings simply do not last in open air sites over tens of thousands of years.

Could those paintings in Colombia be 12,000 years old? There’s no reason that they couldn’t be. But if they are those paintings are both the oldest and best-preserved open-air paintings in the in the hemisphere. Until someone can either directly date the paintings or explain their remarkable preservation, claims of Paleolithic origin will be hard to accept.